A Conversation with: Joseph Awuah-Darko

Joseph Awuah-Darko, founder and director of the Noldor residency in Ghana, discussed his entrepreneurial journey and development of the residency with the ISE-DA team.

Joseph Awuah-Darko.

How did you begin your entrepreneurial journey?

I started while I was at Ashesi University. [I was] working with the World Bank’s Climate Innovation Center, a social enterprise dedicated to Africa's largest electronic waste dumpsite, Agbogbloshie. There were about 20 to 15,000 lbs of e-waste illegally dumped there per annum. The first time I went to the dumpsite was with a contemporary photographer from Ontario, Fabrice Monteiro. He was doing some work at Ashesi University and wanted to work at the dump site. He asked for volunteers and that was my first encounter with a dumpsite. [Agbogbloshie] was this nascent, underdeveloped area that did not have any private or public sector interest. There was no mandated interest to create any social change in the space, even with about 40,000 low-income inhabitants currently to this day. I worked with Cynthia Muhonja, a fellow student from Ashesi and MasterCard Foundation scholar, and the team to conduct ethnocentric and empirical research. We worked to find ways to upcycle meaningfully, [turn the waste into art], and create more sustainable space solutions. That was my experience in social enterprise while I was in University.

I think the natural progression from that was to follow my passion, and that has always been art, African contemporary art, specifically. I have always had a unique affinity for contemporary art. Following that experience at Agbogbloshie, I chose to go to London to study at Sotheby's Institute of Art and then start to learn more about contemporary African art ecology. As a creative, who had an exhibition at Gallery 1957 in February 2019, I wanted to know what facets of the art world I did not like or want to be involved in.

I tried my hand at every single field. I worked at the Sulger-Buel Gallery, volunteering for a year. I had great proximity to the Tate Modern as my friend Osei Bonsu was there. Then COVID-19 happened. I returned to Accra and had this awakening. The [lockdown] exacerbated opportunities for artists in an already under-invested sector, which is the arts and culture sector in Ghana. I thought “I can no longer be passively involved as a collector or as somebody who only deals in the secondary market of the art world. I must now take a more proactive stance.” I knew that I did not want [to work in] a gallery. While galleries are an important part of the ecosystem, I wanted to play a much more nurturing but still commercially aware role with artists from the region. I found this space, a post-colonial building, in Ring Road East, and signed a 10-year lease. I [told myself] “This is where I am going to create a space for creative proliferation and support artists. [This is where I can help] nurture their careers and guide them.” Now here we are, 15 employees later, a few major donors, and five artists currently working with space. I have almost taken a corner of the continent and Ghana's art ecology. It has been refreshing to see the progress.

Noldor Residency Building. Courtesy of Noldor Residency.

What issues did you identify in the art ecosystem and how have you tried to address those within the residency program?

There is significant underinvestment in the arts and culture scene here, in Ghana. We have no institutional museums; they do not exist. We have a few foundations and spaces like Ibrahim Mahama’s, SCCA (Savannah Centre for Contemporary Art), and Red Clay studio in the north. We have the Nubuke Foundation. Then we have Noldor, which is less than a year old. As far as non-commercial spaces that are dedicated to purely supporting artists in a meaningful way? We do not have that. There was a clear pain point that I had to address. That is what [Noldor] was going to address and that is what we have demonstrated.

I have an example. Emmanuel Taku, our pilot artist in residence, was practicing as a teacher. He was an artist for a decade but was [unknown] to the market. Then, because of the residency, he created work in a large format for the first time. He received books and access to resources that allowed him to deepen his practice. He became canonized in the market because of the residency, has this exhibition at Maruani Mercier Gallery in Knokke, Belgium, and sells out in 30 minutes.

We have been an investment, a catalyst to incubate potent, emerging artists from the region. At first, galleries would only invest in artists they knew how to market and who had their own media. As you know, galleries rarely take risks because it is a commercial model, as opposed to one imbued with empathy and is human-centered. I have been adamant about incorporating this into the residency’s DNA - we are human-centered and focused on the artists first. I respect galleries and what they do but there are limitations in the model itself.

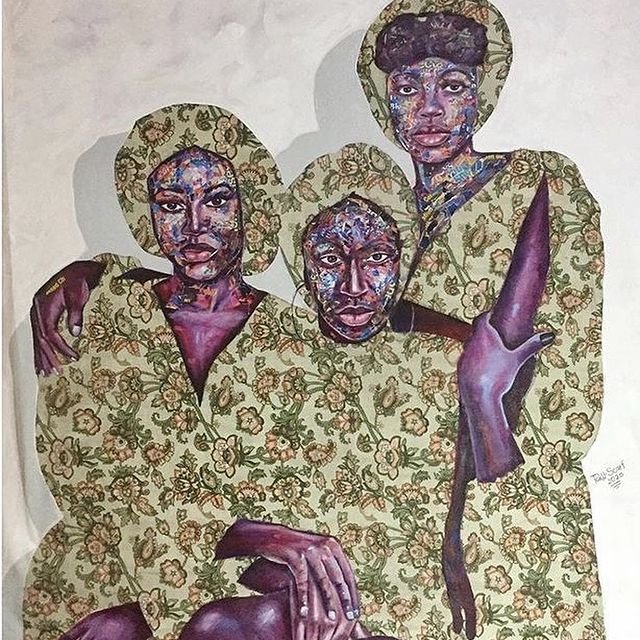

Emmanuel Taku, The Three Damsels

You mentioned it is important to work with artists and nurture them. What kind of mechanisms do you put in place to help protect the artists?

We have our in-house counsel and a formidable three-woman financial team. We have a data manager and an artist liaison for each of the artists.

What we have done is equip them with legal, infrastructure, and/or logistical tools. For example, we may facilitate sales on the artist’s behalf and implement no resale clauses when dealing with collectors. We ensure that even in building their visual language, they uphold artistic integrity now instead of simply doing what the market wants. We make sure that they have fun and are also building a solid conceptual framework.

At the same time, we like to be organic - I have a very nuanced and specific unique relationship with each artist. I accept that they are all on different trajectories. No two are the same and I can never treat them as such. Emmanuel Taku is very different from an artist in the Ivory Coast I recently visited, Cathlene Masane. We always have a male and female junior fellow.

We know you are a part of Artnet’s Africa Present initiative. How do you see this helping shape the contemporary market in Ghana?

Art will always fit a market context. It is very reductive to see money as a bad thing because it is a resource that facilitates [growth]. I encourage artists to understand that and engage with the market, in being represented, and having what I call healthy inflation in their pricing. [Artists] gauging demand and controlling supply to receive what they're worth is important instead of fulfilling the unimaginative trope of a starving artist and not understanding [market forces]. It is important to have players like Artnet involved in a market capacity in what is a very fresh African contemporary market space. I am also dealing with a very exciting NFT artist, Kojo Gyan, who will be an interesting person to watch. We are trying to become the first residency to open our doors to digital artists. As a new [organization], we are running a very inclusive avant-garde model. That is the beauty of artist residencies. You have to adapt to the context you find yourself in and the geography.

Would you be the first residency to house an NFT artist in Africa?

I think so yes. We would be the first on the continent to house an NFT artist.

Had you worked with the artists before the residency?

I had not worked with any of the artists [before Noldor]. I met them for the first time at the residency. With COVID-19, I could not do studio visits, I had to use my trained eye and I found the artists on Instagram, like Emmanuel Taku. I realized that he had studied at Ghanatta College of Art and Design in Accra like Amoako Boafo. I also realized after I had collected his work that he was technically trained.

Courtesy of Noldor Residency

You started as an art collector. Are you still building your collection?

I think being an art collector is very perennial, you do not start and stop. The frequency of what one collects varies from time to time. You have to be selective. I do collect actively but it is very calculated. I am trying to collect more female practitioners moving forward as well. It is not like the early stages where you buy more frequently to build a collection. It is more like a home trotting, not galloping.

What advice would you give to aspiring collectors?

It is very important to find pieces that resonate with you as far as your narrative, that identify with your sense of self and what you represent. At the same time, be smart about collecting, knowing that it will be deemed, in some form, as an alternative asset class. Only buy work from artists you truly believe in.

I tell all my friends to get an advisor. They will point your eye in the right direction, on the right spectrum of what to like, and what to select from. In the beginning, be selective about the advisor. You want somebody who already has skin in the game.

Do you have a plan for your collection?

I have thought about what I would do. I think my youth comes into play here. When I settle down, I will think of where to gather it and give it a name that means something to me. In the long term, I probably would want to donate it to a museum.

What future do you see for contemporary African art?

I think that contemporary African art is one of the most exciting spaces right now. It has gained this renewed international awareness and acceptance, not that it needed it. But it feels good to be part of the broader dialogue about the $65.4 billion art space. There is a lot of room for exponential growth and for many of the other practitioners in this space to reach the levels of their Western contemporaries.

In full transparency, when dealing with the artists, you will find that most [collectors] range from the political elite to heads of enterprises. They are the only Africans in our database who are collecting. I think that is slowly changing.

We will see many more collectors who have more of an interest than the previous generation in what it means to be a collector. They might start more passively at first, but we are seeing a new vanguard of young collectors looking to be a part of the space. We also have a new generation of young people interested in being involved in a meaningful and sustainable way. We need more collectors from our own communities.

I am excited about that as well. I am also happy to be part of what you are doing. It is interesting to see you are creating space for these discussions. I am happy to have been part of this.