What You’re Getting Wrong About the British Vogue Covers

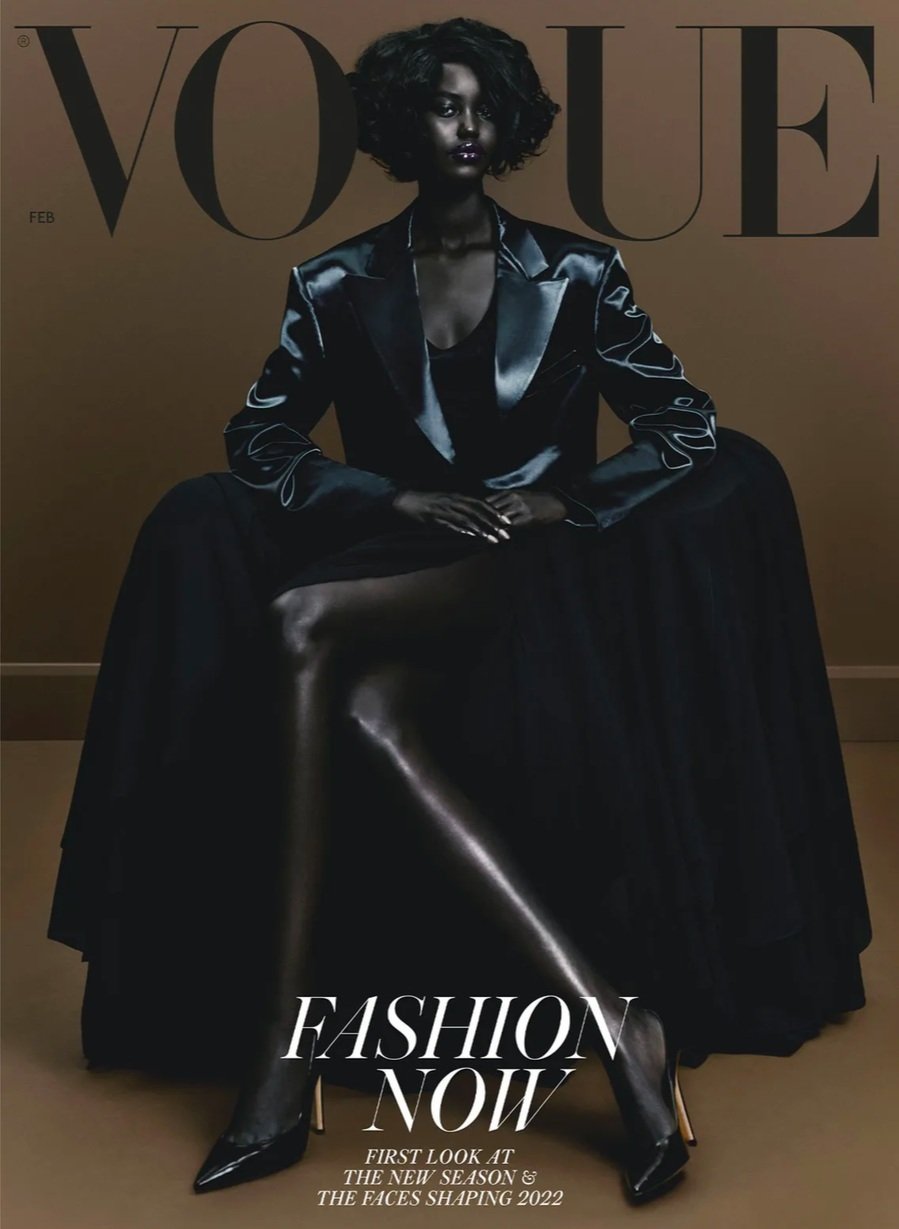

British Vogue dropped their February 2022 issue by revealing covers featuring nine dark skin models of African heritage. According to British Vogue Editor Edward Enniful, the purpose of the issue was to celebrate a new era in which women of deeper complexions take a “meaningful, substantial, and equal place among the most successful women working in fashion today.” Enniful, the Ghanaian-British editor known for his bold efforts to diversify the publication, acted as the shoot’s stylist. The photos were captured by Brazilian photographer Rafael Pavarotti, known for ultra-saturated tones like those featured in this most recent publication.

Like many, I found the cover to be a fresh and impressive yet much-needed disruption to the limits of historically white-washed cultural institutions like Vogue. However, the reception wasn’t entirely positive, with a number of people slamming the work for being offensive and published in poor taste. The critiques of this cover range from claims that the lighting is a travesty to outrage over a perpetuation of negative perceptions of Black women in fashion. One artist said “I am South Sudanese and I can assure you that there is nobody moving around looking like this… I can also assure you that this is not art. This is Black Skin Porn. Black Fetish. Reverse Bleaching.”

As a visual art enthusiast, I live for the way that these kinds of discussions unfold, particularly when they center on Blackness. As a former magazine editor, I am especially fascinated by how viewers engage with cover art and how they interpret the creative choices that go into these covers. While critique is a key part of how we experience art, many people are missing the mark with this issue. It seems to be lost on folks that photography can be an imaginative visual art medium like paint or sculpture. The point isn't always to be perfectly realistic. In fact, it is the surreal nature of the striking blackness in these images that demanded my immediate attention and awe. Shouldn’t we interpret this work in the same context as the range of existing works admired for “unconventionally” portraying Black skin?

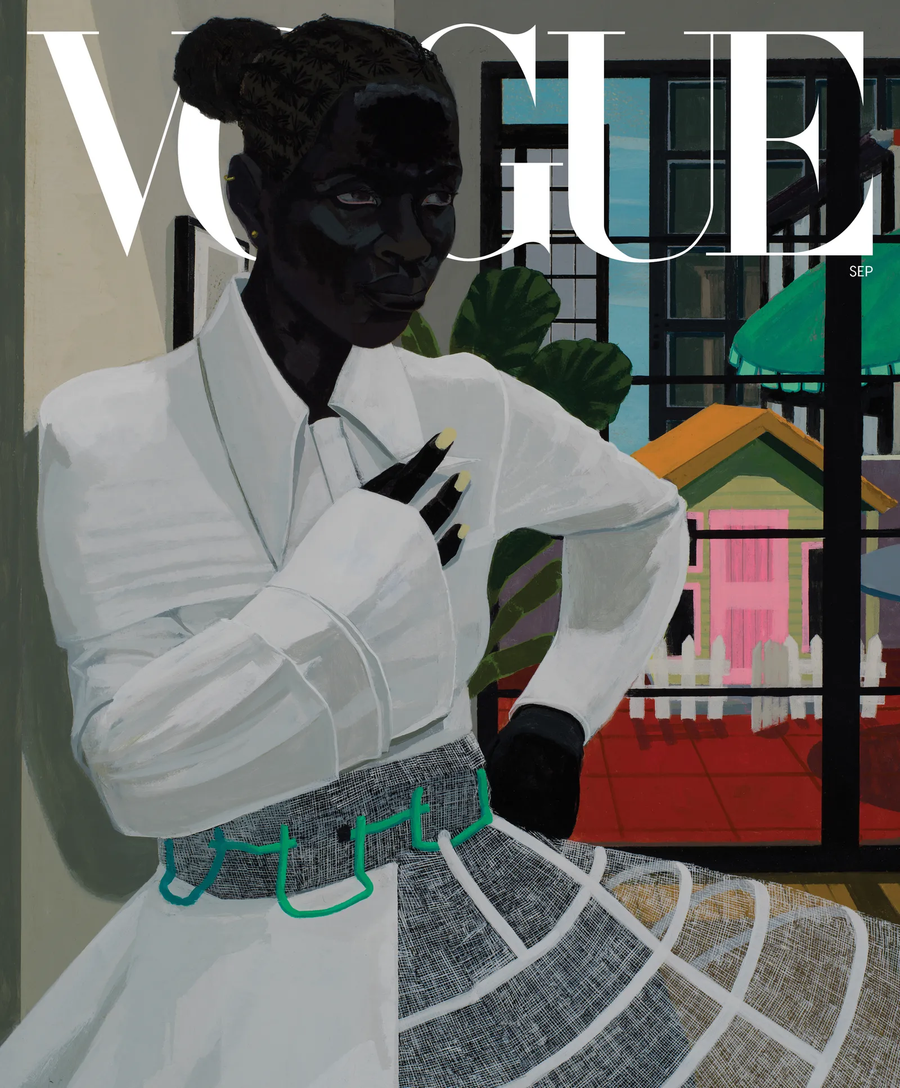

Perhaps one of the most influential visual artists of our time, Kerry James Marshall, painted a woman in a similar style for the American edition of the same publication just under two years ago. Marshall describes the fictional character at the center of Vogue’s September 2020 cover as having skin so dark that it is “at the edge of visibility”, an approach that is consistent across all of his work. This style has been praised as a “rhetorical statement about Blackness itself—not realistic but didactic”. Marshall says that, in his work, he aims to show that “black is richer than it appears to be, that it is not just darkness but a color.”

Amy Sherald, possibly most well known for painting Michelle Obama’s official portrait, has spoken at length about her own unorthodox technique to painting Black skin. Sherald explains that she is deliberate in her intent to “interpret the rich complexity of Black skin in gray tones” rather than traditional brown ones to break against the centering of identity. For both Marshall and Sherald, two artists who exclusively portray Black people, the tones they choose may not be true to life, but they are stunning nonetheless. And it is these artistic choices that have cemented them as trailblazers in the canon of Black visual art.

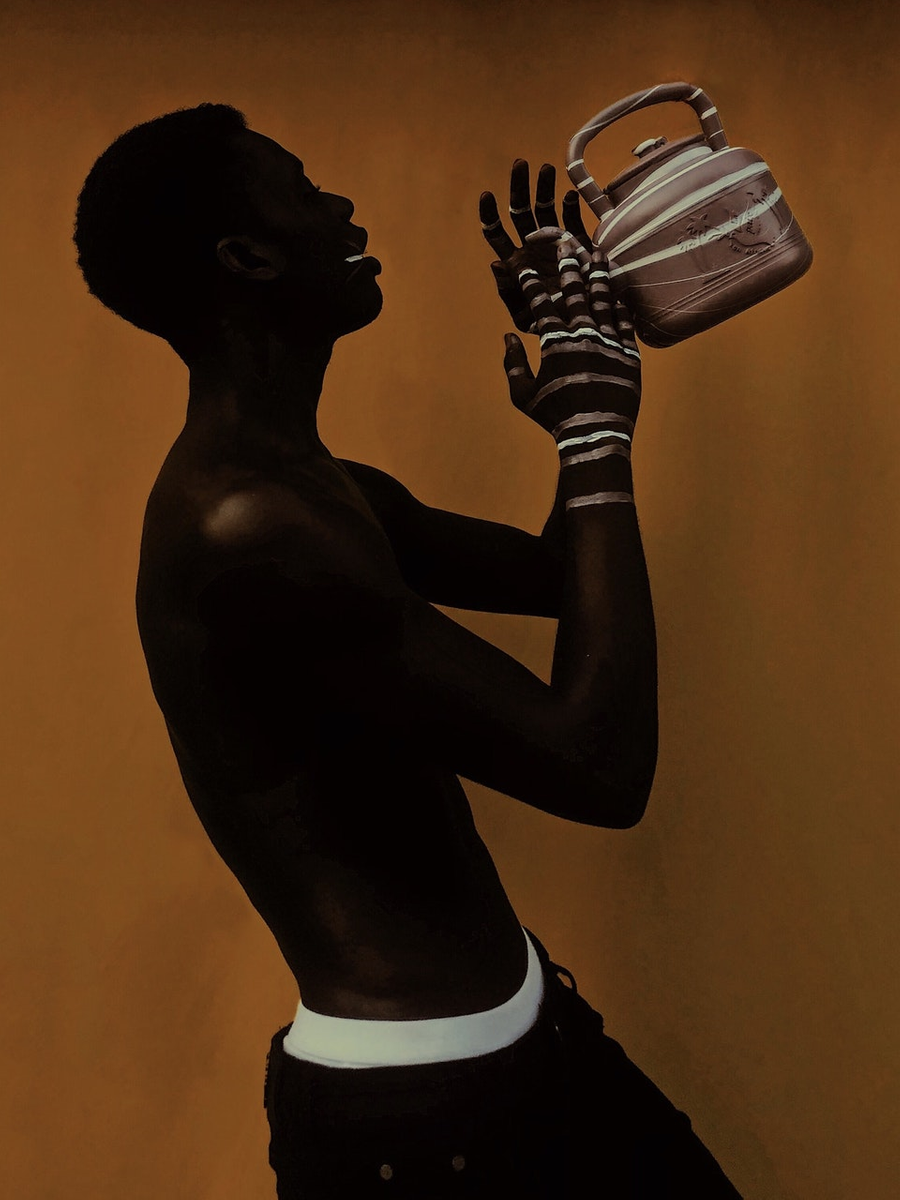

British Vogue's most recent issue is neither in poor taste nor is it new in its style, even within the medium of photography. For Ghanaian photographer Prince Gyasi, deepening the skin tones of his subjects to embrace the contrast against their surroundings is key to his bold approach. For Ivorian and Senegalese artist, Aicha Fall, the surreal techniques she uses are a significant part of what makes her work so compelling. In some instances, the blacks are so dark the figures almost resemble a Kara Walker silhouette. In others, she abandons a resemblance to reality altogether by editing the skin with colors like violet. For both Gyasi and Fall, manipulating the photos in this way makes them all the more effective storytellers as they highlight Black skin against the vibrance of their environments.

Prince Gyasi

As a dark-skinned Black woman who works in the creative industry, I am all too familiar with the struggles of lighting Black skin, from inequitable technology to inexperienced photographers. I understand the urge to speak on the British Vogue cover for the sake of colorism and representation. However, there is a difference between tragic lighting choice and a deliberate artistic interpretation of Black skin. Sometimes art deserves more than superficial engagement with topics as serious as those being debated. This is one of those times.

Adama Kamara is a creative strategist and writer based in DC. Adama leads content and programs for ISE-DA. George Kofi Prah is a graphic designer, illustrator and visual artist from Ghana, based in New York city. George leads visual design and art direction for ISE-DA.