A Conversation with: Nyareeta Gach

South Sudanese artist Nyareeta Gach discusses how her work reflects her personal and political history in this interview with ISE-DA.

Could you speak to us about your upbringing?

I was born in 1992 and I'm the eldest of my father and mother. I have four older siblings. All [my family had known] was war. My father feared that we'd experienced the same thing and the war was moving from west to east. He decided "Okay, we must move to America." Around that time, it was a very hard decision for my father to make. He was also a politician.

At nine months, my mother strapped me on her back and they walked. They walked from Maiwut, which is in Upper Nile State of now South Sudan, and they walked down into Ethiopia to the first refugee camp called Pinyudo, which is in the southwest. In Pinyudo, they started the application process, but through translations, a few things were missed. The family was too large - it was seven of my father's siblings, my mom's older brother, the two of us, and then my dad's four kids and my dad's other wife. They rejected our application. We went back to the bush, you know, as they say, which is back into the wilderness. A lot of my memories are suppressed, but they come from that. You can see it in the art, which is this up close, intimate, but displaced interaction where it feels like you've encountered something, but it is not tangible.

[After that], we then went to Addis Ababa, we had family there as well. My father wasn't satisfied with staying in Africa. He wanted to move us to America. We went down to the Kakuma refugee camp, which I believe now is still one of the largest refugee camps in the world. At that time, there was a large rescue of Lost Boys. So that attention and the service was given to the Lost Boys, of course. There was also a lot of tension because of rival factions and issues of tribalism. Again, we left and we went to North East of Kenya, to Dadaab, where there's a refugee camp called Hagadera, which was housing a lot of Somali refugees. So, I grew up in Hagadera, and that's where I went to school. From Hagadera my father would leave for political missions, and my mother would do the same as well. I grew up with my other mother. There were times where we would, as a family, leave the refugee camp and we would go to Nairobi, where they would have meetings, and we would go to school.

Is this also included in your work?

Yes, the memories from Hagadera are seen in a lot of my work as well. There is a series that I call Hagadera, which is the notable red Earth of Kenya. It stands out because I have always been the child that was in isolation and would wander around. In Africa, you have responsibility for yourself as a child. I would always wander and seek nature. That is very prominent in my, in my work. In 1998, I believe, our family was accepted for migration to the States. In 1999, there was a fight that happened back home in Southern Sudan. My father came back and he was amongst the elders. Anytime there was something that was going on back home, he was called to come and mediate.

There was another incident a year later. Around that time, it was a problem that would be reoccurring. My father decided the family had to separate. He said, "You are going to go to America, and I'm going to stay here and I'm going to go at a later time. These situations are not going to let up if we want to see the independence of South Sudan". So that was that. We had our plans, and we would come to America and get our education. A few months later, there was an altercation that happened in my father's village that needed to be solved immediately.

My father and uncle left [to my father’s village] but he missed his flight a few times. They decided to go back. That night, he was crossing the street from the hotel they were staying at. He got hit by a motorist and was killed immediately. That was two months before we came to the States. It was this tragedy that we didn't have time to process.

I think that's part of the embedding trauma that I believe is this bewildering gaze in the work that I produce. [It is this] very intimate, and inescapable grief, agony, these very high-strung emotions painted by these bright colors that illustrate childhood. But I didn't have the time to process and know I had experienced a great loss. It was like "that happened. Let's move on." So, I've always had to look at life through the vibrant pursuit of surviving, of just going on. With my artwork, it's a moment to stop and look in a mirror to see these kinds of placements. It becomes almost like a film, where everything is one singular shot, one shot after another shot. The more you stare at it, and the more that you're looking into it, the more you can kind of perceive it and want to understand it in depth. But it's limited.

Monopoly, Acrylic and Oil on Canvas, 24in x 30in, 2017

Have you always been drawn to painting to express your past?

I have always been drawn to painting, but I started my journey with poetry when I was 14. It was a way of tapping into unearthing those feelings because, at some point, I realized that it is not healthy to not express grief. [It is not healthy] to move about as if something never happened. It is going to affect you, whether it's conscious or subconscious.

I took a lot of classes, a lot of electives that were art-oriented. I had a teacher who noticed that I was talented in painting and drawing. She tried her best to nurture me, but I was also a shy kid. I would do exercises with her where I would paint and draw bigger and bigger because everything was very small. That was my comfort. She nurtured me. I was doing a lot of after school activities as well as community service. So that was my passion as well, activism.

I went to a Technical High School, meaning that you declare your major or whatever you wanted to do in life, a little earlier on. I said I wanted to do something in the arts, but I also wanted to do teaching, to satisfy my mom a little bit. In the back of my mind, I thought "No, I'm not going to do that,” [even though] it was something that I had a passion for as well.

I found this great school, RM CAD, Rocky Mountain College of Art and Design in Colorado. I was very intrigued by it. I didn't think I would get in because of the tuition fees. It was a whimsical decision but I did it and I got in. It was the only school that I applied to. [I put] all my chips in and I was accepted. I was mystified and I thought "Okay, I just took a huge gamble and bet on myself. What next?"

I declared my major as teaching with a minor in illustration. I took the first class of teaching, and I realized this was not for me. For the first hour and a half, I sat there just thinking about all the negatives and how I didn't want to do something that wasn't fully my choice. I wanted to make art to express my feelings, to tell stories, and to share my history. I wanted to document not only what had happened to me, but what a lot of people from South Sudan were experiencing from the trauma of war.

I have noticed through your social media, it displays your work, but it is also an archive of political and artistic history in Sudan. Is that something you aim to do through your social media?

Yes. It comes from that place of not wanting to be in an educational institution teaching. My comfort is doing that through social media. That archive is also to teach and to give people another history we never had. For us, when it came time to learn about Africa, it was a three-week crash course. Social media allows me to have those supporting images, those supporting statements, and to make it shareable and visually appealing. It also aids as a reference to my work. I enjoy that, I enjoy giving people the option of then going to learn for themselves.

What is your process of developing your work and projects?

I don't necessarily sit down and try to have an idea. It comes like a tide of emotions.

The project that I'm working on is to honor Angelina Denton, who is the wife of the Vice President of South Sudan. She was the one that advocated for him to get his passport after he was deemed as a rebel of South Sudan. She worked tirelessly going from Ethiopia to South Sudan, to South Africa, to Kenya, really working kind of in the shadows to help him come back to South Sudan. At that time, there were a lot of tribal issues that needed to be resolved. If it wasn't, we would be seeing another generational war in Sudan. There would be a repetition of what we went through dealing with North and South. So, with that, it came about from like the current climate of South Sudan, where we're seeing another resurgence of tribalism. And there's a lot of killings still, but it also relates to the other series that I started, "the Death of Journalism" because there are no journalists allowed in South Sudan currently, you know, there's no one to speak on these issues. I see my art as another way of journaling, telling these stories, so the world understands that in South Sudan, we're trying our best to overcome, but it's a very corrupt country. And if you speak your truth, you're facing death. Even here, sometimes I think "maybe I should keep my mouth quiet on these things." But I took the year to be okay and not to fear.

Divide & Conquer, Acrylic and Oil on Canvas, 18in x 18in, 2018

I know that your artwork and your activism was one of the reasons why you were part of the project with Mark Quinn, the 100 heads project, so would you be able to speak more about that?

I was nominated by a brother of mine, Bafo. It was an amazing opportunity. Just to share a brief statement of why refugees should be seen as human beings because especially through this [past] presidency, there's a great fear of immigrants. To be honest, it never really occurred to me like that until now. As you know, when you're acclimating to a different country, you're trying to learn the language, and you're trying to assimilate, you try your best not to think deeply about how different you are. You just want to relate. [The project] was an opportunity to share that. Many people in this world are refugees, that are trying their best to give new hope to their families and themselves as well, and remain rooted in their cultures. I don't think people realize the sacrifice it takes to leave your country. It was a great opportunity to share myself.

As an artist, a poet, and activist, what other resources are you hoping to use to continue to share your story and grow who is receiving your message about things that are happening in South Sudan or across the Diaspora?

I would say currently, it is about having representation. I want to broaden myself and I have been thinking about seriously looking into residencies as well. But it's really about representation. I think once that happens, it will be easier for me to move about and be taken seriously. If you don't have representation, people perceive you to be a hobbyist of art, you're not really an artist in their eyes.

What residencies were you considering?

I was seriously thinking of applying for the Black Rock Residency. But I worry a lot about my family as well and taking care of them. I am using this year to be here for my family because I have younger siblings as well. In a sense, that kind of limits me but I don't limit myself whatever opportunity comes that is appealing to me and is right for me. I'll take those on.

Do you collaborate with other artists? If you don't, is that something that you're considering?

I don't at the moment, but I've considered it before. I've also been trying my best to re-integrate myself into the art community. I took a long hiatus after college. It threw me off-balance with keeping up and being around other artists. But, I do enjoy it, especially when I was in college. I enjoyed the work of group critiques and the banter. Now that I'm back in the groove, I would like to collaborate, and also to have conversations like this. In the past year, when I was in Brooklyn, I was doing a lot more of that. But you know, New York is so hectic, where you do have to have a few jobs and a few gigs. It felt like I was in a mode of survival rather than being in this place that I came to reintegrate myself into the arts and find myself back, grounded as a professional artist. Even here, I've reached out to a few friends, one that I thought was in New Mexico, but he's moved. He's given me some great contacts here in Phoenix, and the museums are opening up soon, so I'll be able to kind of venture out find some folks.

You were recently part of an exhibition focused on supporting those who are underrepresented. Can you provide more details about that experience?

The exhibition with MvVO Art. It just recently ended on September 29th. I received an email out of the blue, saying that I was nominated to partake in an exhibition highlighting unrepresented artists. It was a segment called "Don't silence our Voice" that showed unconventional artists and Black artists to provide exposure also for the Black Lives Matter movement. It was incredible to have that. I was very honoured and grateful for that. It was at the Oculus at the World Trade Center and was on screens throughout the Oculus for about 23 hours. [My work] would play every eight minutes.

From that, I have my work on Artsy for the entire year so I would be able to sell that artwork and others they have included. I am still processing it because it was an amazing experience. I think I know who might have been the one responsible for nominating me. I am not sure yet. But I am grateful.

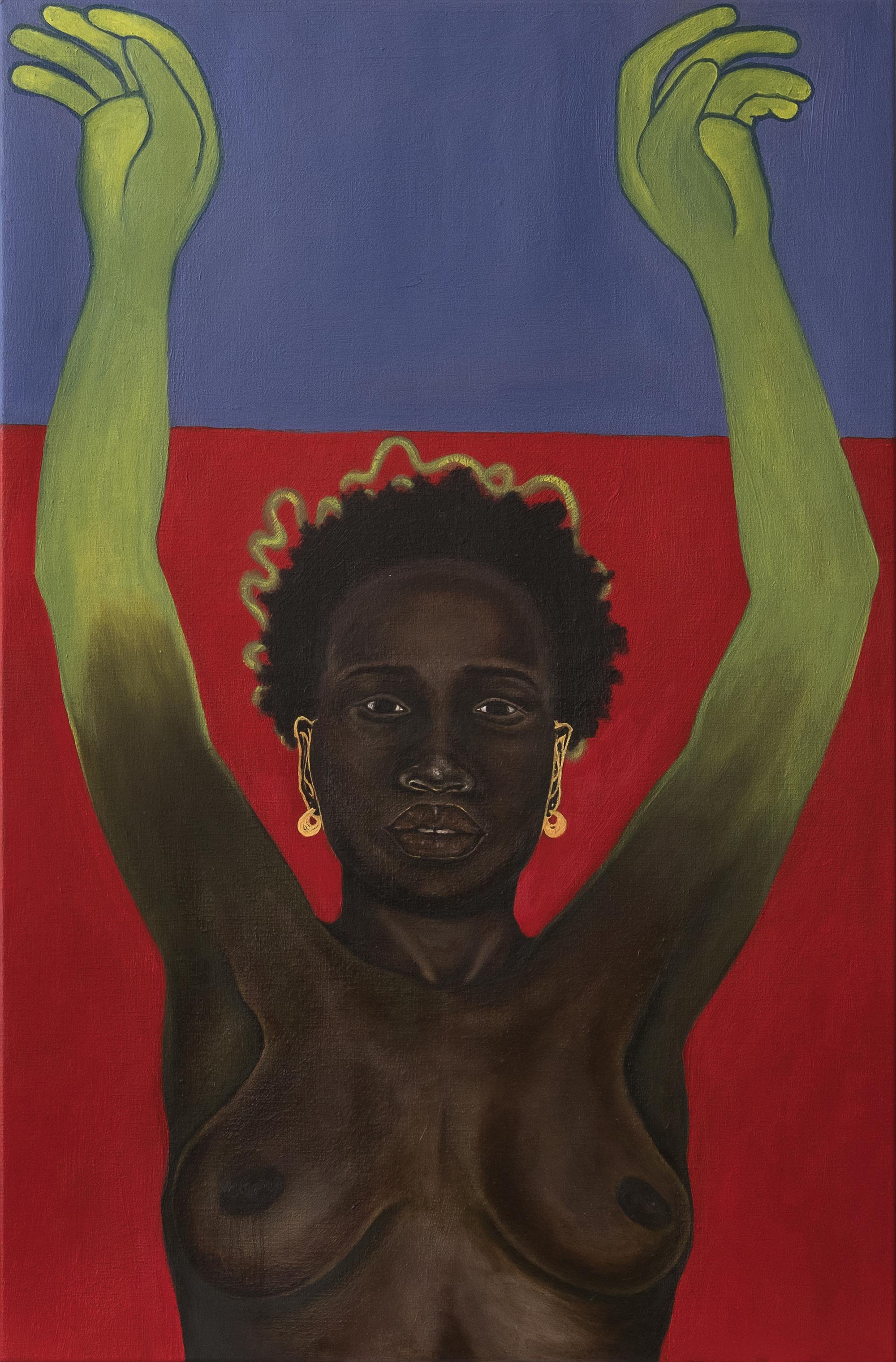

Daughter of a Song Bull, Acrylic and Oil on Canvas, 24in x 36in, 2018

As an aspiring gallerist, what would your mission and purpose be? When do you think that could be a vision that comes to fruition?

The idea of the Ngun gallery came about in May, last year. I was thinking about how when I was in school, I didn't know any other Sudanese artists. I would look online but it would only give me vague ideas, there was not anybody particularly notable, there were just images. So, I took the time to research and I realized there are a lot of South Sudanese artists here and back home, as well as in Australia. I sat down and told myself that I did not want it to just be a platform, but if it is just a digital platform for now I am satisfied with that. In time, maybe 15 years from now, I want to have a physical space in South Sudan. I want it to be a gallery. I also want us to start thinking seriously in South Sudan, about museums, because we do have a lot of our "artifacts" in museums such as the Pitt Museum, the Museum in London, and a few others. A lot of these "artifacts" need to be where they can be viewed by all South Sudanese visitors, and others as well. That was the idea.

I also realized that we don't take art seriously in South Sudan. But I think, in a way, in Africa in general, but attitudes are changing. It is the traditional art that I think a lot of people turn away from. With digital art, especially in the South Sudanese community, people understand it, they understand that it can be used for marketing, logo design, and more. The understanding of the traditional art, the painting, the sculptures, it makes them not necessarily uncomfortable, but it's hard for them to accept. But music? Music is like, the top tier of artistry in South Sudan. Then modeling, if you're doing anything alternative, and then sports.

I think that's a really interesting point. I've always thought it fascinating how sports and music and gaming has been able to capture the attention of a lot of people across generations, both in and out of the industry. I wonder what is the art industry missing.? What will generate that sort of consistent interest and support?

I think it's the language is the language of art. If you are going for nursing, or to be a doctor, you have to understand the language of it. It's the same thing with art, it's the language and that barrier. It is also the culture of the institution.

I think people believe “if I'm not an artist then I don't need to know about [the industry] or involve myself if I have no interest. With sport, in particular, there's participation. You're cheering, you're playing, you can coach - it's projected differently. With modeling, it is the aesthetics and it moves from the brand to clothing, to news, to the photography from the shows and the magazines. It's that the entire institution is developed to appeal to the mass. I think art doesn't really - it's not directed to the masses in that way. If we made it okay for everybody to go to the museum and it was accessible for them, then we would see the culture differently.

It is just extremely detrimental to the art industry that it's pushing this inaccessibility. I'm hoping with what has been happening over the past few months with Black Lives Matter, with museums being critiqued consistently and interrogated about how they navigate, change will come.

What do you hope to see next with your career?

I want to see my work in galleries and major museums. I want to do more artist talks and that kind of thing. I want to be in those major platforms and those major institutions and share, but still, come back to the studio and have a studio of my own.

Forrest, Acrylic and Oil on Wood Panel, 8in x 10in, 2018