Freedom, Community, and Unity: Nelson Stevens’ Insight into the Black Arts Movement

As part of our “The Art of Black Liberation” series, the ISE-DA team sat down with Nelson Stevens, member of the Chicago-based art collective, AfriCobra. We discussed how he became a part of the collective, the importance of creating for community, and his travels as an artist.

How are you?

Copacetic. How are you?

I’m doing well. We’re doing a mini-series on the art of black liberation across the diaspora and one of our focuses is the Black Arts Movement.

Are you familiar with the work of Carl Owens? He did a poster, about apartheid. And, he had small figures. Well you didn’t think they were small figures, from a distance they looked like notes. Music notes. You get closer, and you see that they were individual small figures. These figures were like a half inch high. And maybe there were eighty of them on each line. And it was dedicated to 250 black folks that were sacrificed in South Africa for apartheid. I thought it was a very dynamic way of dealing with it. I wish I could show it to you. I do have the poster in the house here. But if you can find it, you’ll see exactly what I’m talking about. Carl Owens passed away maybe 10 to 15 years ago, in Atlanta, but he came to prominence in Detroit before moving to Atlanta for about 15 years I guess. But why don’t you start with what we want to do?

Could you speak more about the philosophy of AfriCobra and how you become a part of it?

I had done 6 years of teaching in the Cleveland public schools on a junior high level, and with the museum. They have a great museum there - it still is one of the richest private museums in the country. And, I took a leave of absence to work on a degree at Kent State University, which was about 35 miles away, towards Akron. I graduated [with an MFA] in 1969. But in the beginning of 1969, I went to the College Art Association Conference, which is where you go to get a job on the collegiate level. I think it still works that way. And now it’s in February. And that’s where I met Jeff Donaldson, and David Driskell. And David Driskell was busy trying to get the College Art Association Conference to break down some of their walls, so that more people, black people, could participate on the collegiate level. There were hardly any. Jeff Donaldson, I met. He was tall and rangy, and 6 foot 6 or 7, and I ran into him in the hallways, on the staircase, and I was two steps above him, which made us almost level. And we looked at each other’s slides. And he looked at my slides, and told me I ought to get a job as close to Chicago as possible, because that was ground central, ground zero, for the Black Arts Movement. Now, I hadn’t met him before, but I read his name in Negro Digest, and read about him in Ebony Magazine 1967, the summer issue dedicated the Wall of Respect, and he was a major part of it in Chicago. When I got to Illinois, ‘cause that’s the job I accepted, I got in touch with him and he told me about the AfriCobra meeting, and I went by, and I saw the work of Barbara Jones, Wadsworth Jarrell, Jae Jarrell, Jeff Donaldson, and Gerald Williams. And I was really turned on by the majority of the work.

The political ideology was, by and large, supplied by Jeff Donaldson because he was a scholar in black art and in, more importantly, African art. He had collections of African art. He was the first black person I knew who had collections of African art. I went to the meeting and showed them what I was working on. They liked what I was working on. And I became a member in the summer going towards September of ‘69. Now basically what it was, the ideology, there were a lot of little different components, such as Kool-Aid colors and it was about uplifting black people. For example, one of my favorite painters has always been Francisco Goya. Not as a painter, but because of his prints. He did three different series of prints. The one that attracted me most was the one where the French had invaded Spain. There was a war going on and there was an image that he used a lot, and that is of two men carrying one man. Like one man had the feet and the other one had the arms, and they were carrying him off the field of battle. I used that, and Jeff explained that that was just the kind of image that we were trying to get away from, because that would represent defeat. I always kept that as a way of choosing what AfriCobra was about, because although [that image] was about two helping one, it was also about losing.

Those were the demarcation lines. So I joined, and what I was specializing in mostly were heads. I took canvases that were 5 by 5 feet and painted heads of black people on them. In the Renaissance, if they did a head, the head would occupy maybe 40%, 30%, of the whole composition. The head might represent 50% of the composition in a seated position. But it never occupied 80 or 90%. I decided I was going to occupy 90% of the canvas, with these heads of black people and not use brown paint to do black people. I was going to use abstraction to represent black people, and to use pure color. I’d use pure orange, or pure red, or magenta - never pink, which is diluting the red, you know. Hardly ever a sky blue, I’d use the blue more intensely, I’d use purer colors.

At that point in time, I graduated from Kent State, and I was doing more than a 40-hour week of painting, and I continued that in northern Illinois for a couple of years. I wasn’t able to continue it much longer because it was tiring, you know, it wore me out - the mixing, painting, you know, collecting photographs. Because I’ve always worked from photographs. And I always painted the right proportions, I didn’t exaggerate any proportions.

What made you decide to work from photographs?

I decided to do that because I like drawing. I’m a masterful drawer. Charles White is probably the best. I met him, and I always liked the way he did black people, with a lot of dignity. And looking at them from a lower vantage point, to give them a heroic perspective. I met Charles in 1970. He drank scotch, ‘cause I went and got him a bottle of scotch, and pretended like I liked it. And we sat up for a long time, talking about art. A great conversationalist. Particularly at that time. He was originally married to Elizabeth Catlett.

I love her work

Yeah, I also loved her work. I knew how to get in touch with her, and we had long talks. I like talking to some of the great ones, and I’ve had a great opportunity to do that. That’s why I’m in mourning right now, basically, because of David Driskell [passing]. He was the first person to give me a one man exhibit at Fisk, when he was the head of the department there. We continued a relationship over the years, because he went to all the conferences. I went to all the conferences too. The basic reason I went was to collect information so I could teach my students. Because maybe an hour conversation with Driskell, you know, would give me material for a week [of lectures]. I always gained a lot of information, in brochures and drawings, all kinds of stuff. But that was one of the reasons that I went to the NCA. There was an organization called National Conference of Artists, NCA. But originally, when I joined, it was two Ns - National Negro. And one year, we had enough votes to drop Negro, so it came out National Conference of Artists. We had enough votes to drop Negro, but not enough votes to put in anything else. It would always be National Conference of Artists, and in the first paragraph it would explain that it was a black organization because it wasn’t in the title anymore.

Right, and if you don’t make that clear, people who aren’t Black might take opportunities from black people.

But this is what I find very interesting too. You know, the marches that are going on now are highly integrated. A lot of white people. When we had marches there were white people, but there weren’t nearly as many. But we had signs that said Black Power. It’s hard for a white person to carry that banner. Black Power. It’s easier to carry Black Lives Matter.

Do you think that’s why there’s an increase of white people in today’s current movement because the message is a bit more palatable?

Yeah, that and the fact that they can see more clearly the injustice that we have been talking about, because of all the pictures. 30 years ago, we told them about it, and there’d be no pictures.

I know that mural creation, especially with things like the Wall of Respect and in AfriCobra, was very central to those movements and we see a lot of Black Lives Matter murals popping up across America.

There were murals in the United States before that mural [the Wall of Respect] but they dropped it to WPA. The WPA had a mural program. It was well integrated, and several black painters were a part of it, but it died in the ‘40s and ‘50s. Then all of a sudden in the ‘60s, ‘67, came the Wall of Respect. And I think, you know, the other bookend for that is Black Lives Matter, which is outside the White House right now because that is a mural. There’s a great book called Walls of Heritage, Walls of Pride, which covers the mural movement, which is really very good. But it ends in 1980 maybe. If I was doing a book right now on murals, I would include Black Lives Matter. I loved the mural they created for George Floyd’s funeral.

With the Black Lives Matter murals, there’s been a lot of critique that says that by painting the murals we’re taking away from the actual demands of the movement. What are your thoughts on that?

Oh no, no. I think it enhances the movement. In a permanent way. Particularly because, you know, the mural movement starts in Chicago in ’67. It’s in Detroit, it’s in other places in Chicago, in the Midwest. The Chicagoans did a great job with it. They have a great tradition of murals that comes out of Mexico, with Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Siqueiros. And then they combine it with the Black Arts Movement. Taking over walls, they do a great job on the west coast. Some great painters are a part of that.

Do you think it matters who makes the murals? If it is sanctioned by the government as opposed to being created by the people?

Well, whoever pays for it, that's what it is going to represent.

In a certain sense, you don’t want the government too involved in it. Your work must say something, represent something. Funding is an aspect of that too.

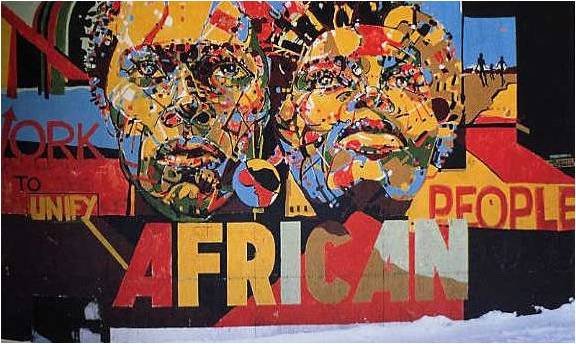

At one point, I decided that I wanted to do murals. I got in touch with Dana Chandler, who was in Boston. I told them I wanted to do a mural. In 1973, he says he’s got a wall in Boston for me. I went down and I worked on a mural. The wall was great. They had put up a wall for us, 30 feet wide and 12 - 15 feet high, and it was a brand-new wall. With some murals, you have to chisel the bricks to make a smooth wall. This was built for us. I rapidly drew two heads up there and started working on them. And I was working with a friend of mine at the time, who was Howard McCalebb, who was a minimalist artist. He wanted to help, so I told him “Okay, across the bottom there why don’t you write African?” I did the two heads, and then I put in the words “Work to Unify African People”. That was my first mural. And because the minimalist concept that he uses is flat, large letters, and mine is very busy with other stuff going on, working and putting the two of them together was a success. It was a good mural. And it was reproduced in lots of places. “Work to Unify African People”. I always liked the sentiment. It displayed some of the AfriCobra principles because we in AfriCobra wanted bright colors, but always wanted words in the composition. So that worked out great as an AfriCobra piece.

On the subject of unification, could you speak about your experience at FESTAC?

FESTAC was the second world festival of Black and African arts in ‘77. Black artists from around the world were invited to Lagos, Nigeria for a party. All. When we were getting off our plane, the Aborigines from Australia got off their plane. We were looking at them like they were the strangest people in the world. They were looking at us like we were the strangest people in the world. People were tripping over each other. But all African people were there and all African artists. I was passing out AfriCobra cards with my work on them one day. Someone comes up and cuts in line in front of everyone. He says “Give me one, I work for Fela”. No one complained. I wrote [on the card] “From one artist to another. I would like to see more of your country.”

I had a great time. I was here, there, and everywhere. I painted with the Aborigines on the street, and I gained an understanding of their art. I drew with a guy named Malangatana. But the biggest thing was I came back to my flat one night, like 9 pm. A guy was waiting for me at the door and asked “Are you Nelson Stevens? Fela sent me. He wants to see you. Come with me. We’re going to Mushin and, if we have time, we’re going to the African Shrine. Where Fela performs for the people.” Fela had the best band and I’ve always been into music. I can’t dance, but I’ve always loved music. I had my AfriCobra posters, and my camera, I brought everything. I was packed. We go to the highway and get to the show. I see Fela and [we talk]. I tell him how much I love Nkrumah and Lumumba and their politics. Nkrumah and Lumumba were educated together and were like brothers. Fela and I became very close when discussing African politics. Fela was very smart, clever brother. I gave him an AfriCobra print which he loved and put up in his compound. Then he explained he was going to the Shrine and if I wanted to come. “Oh yeah”. My camera was ready, I was ready and wide awake. Fela assigned a lieutenant to me to take me wherever I wanted to go for about a week. We went to Benin, Oshogbo, Ibadan, and different places. The artists had the best travel venue because all we had to do is hang an exhibit. The theatre people had to stay together, the dancers too - but us artists went wherever we wanted to go.

Did your art change after your experience at FESTAC?

I began to use the FESTAC mask in a few compositions. But even the mask, the one made of ivory, never left London but it was used as a symbol of FESTAC and unity. My work intensified in many years but I don’t know of a specific instance. FESTAC made me have a better understanding of history by going to Nigeria and Benin. I still have the drawing that I exhibited at FESTAC. It’s being framed right now and will be at my retrospective exhibit.

One of the classes I taught was magazine production. There was one magazine that was dedicated to FESTAC. DRUM magazine was an outstanding student publication, one of the best in the country. When I got there [to UMass Amherst], I always contributed artwork. The students asked and I always did. One year, two years in, around ‘74, the students came to me. They said they had been putting out the magazine for 5 years and some of the politics of the original students had waned. They were not able to put it out that year. They suggested I take it up as a class and structure it. I spoke to my wife and Larry Neal about it, one of the chief architects of the Black Arts Movement with Amiri Baraka. He mentioned an epic poem that he loved, that said:

“Gather the children into the evening quiet of the living room and teach them the lessons of their blood.”

Larry asked me “You think you can do that?” I said, “Oh yeah, I can do that.” And he said, “That’s DRUM Magazine.” So, for fifteen years, I organized DRUMMagazine. I always had great editors. I’m not a great editor, but the editors I got were so good. Years later, when I went to Essence magazine for the Black Christian Arts Calendar, I got off the elevator. This woman said “Professor Stevens!” It was a former editor now working at Essence magazine. By the time I made it to my meeting, I had run into three former students of mine. They were brilliant, geniuses.

A lot of your work has focused on supporting younger artists and creatives. Could you speak about the calendar you produced?

I was living in Springfield. Increasingly, I was going from one funeral to another of teenagers. I decided that they did not see any spirituality. This was years ago. They had this idea that Christ was a blonde-haired blue-eyed guy who looked like a hippie and had no relation to them. I started talking about Black Jesus and I got artists to visually Africanize the Bible. For four or five years we produced art that did that. John Lockhart contributed every year, and many other artists like Calvin Jones and more phenomenal artists contributed. Carl Owens participated for one or two years. I got some of the best artists in the country to participate. Some great art was produced, so good that it was exhibited around the country and a big exhibit was at the Schomburg.

---

I am meant to have an exhibit of 75 pieces of my artwork soon. By and large, they are owned by Black middle-class people rather than the institutions. The size of the work determines where it’s going to go. If you do a 20 x 20-foot painting, you can’t say it's for the people. You are painting for the museums.

So artists creating larger works are not basing their work in community.

People get fooled with that stuff. You weren't doing it for the people, please. But people tend to say that, to run their mouths without running their minds. Make it affordable. That’s why we specialized in silk screen prints. The first time we had a major exhibit was in New York City. At the Studio Museum. We gave everybody a ballot that said: If you could afford it, which work by each artist would you most like to have? When we got back to Chicago, we knew what the people liked. We never painted for the people, we already painted and the people chose what they liked. Some people specialize in the Black family, but I specialize in heroes. Another person might specialize in land. But we had a piece from each artist that the people thought was the best piece. And that was the piece that we made silk screens of. We had an edition of almost 100. Mine was about 80. We didn't charge each other for our labor, but everyone participated on running the prints. We came back for a second exhibit a year later - we had prints to sell, that we knew the people wanted. They were $10 each. You can get one or two of these now for about $10,000 and they’ve changed hands about 30 times.

Does that change the purpose of the art for you?

Black people made money off it and that’s okay. Eventually, it will no longer be in the Black community but in the art community. We weren't thinking that far in advance. But Black people were able to benefit.